The annual gadget bacchanalia known as CES kicks off next Tuesday in Vegas, but as has been the case for the past decade, the most important new product in consumer electronics won’t be there.

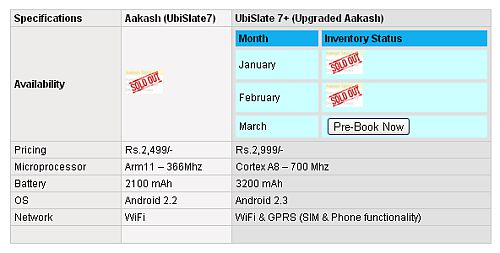

This year’s star no-show, however, wasn’t invented by a certain Cupertino fruit factory, but by the obscure Canadian startup Datawind. It’s called the Aakash Ubislate 7, and its humble specs would cause iPad owners to burst out in hysterical laughter: A 7-inch screen without multitouch. A battery that lasts a little under three hours. A processor that runs at a tenth the speed of iPad 2′s A5 chip and just two gigabytes of storage — all running a four-year-old version of the Android OS and crammed into a chunky case reminiscent of a vintage GPS.

Given its last-gen tech and entry-grade components, you’d probably guess that the disruptive innovation of the Aakash tablet isn’t performance, and you’d be right: The goal of the Aakash isn’t to be great, but to be “good enough” — at the cheapest price possible. In other words, to take Steve Jobs’s words in vain, the way Datawind hopes to put a dent in the universe is by minimizing the dent in users’ wallets.

The Aakash is the product of a competition sponsored by the Indian government in February of this year to develop and manufacture an ultra-cheap tablet optimized for the nation’s 1.2 billion market, targeting a price point below $50. Montreal-based Datawind, founded in 2000 by the brothers Raja and Suneet Singh Tuli, beat out giants like European semiconductor titan STMicroelectronics by coming up with a design that undercut the next highest bidder by nearly 25%. In fact, when the results were announced, CEO Suneet Tuli frantically called his older brother to ask if they’d accidentally miscalculated their costs. CTO Raja assured his sibling that they hadn’t: They’d won the bid. Now all they had to do was deliver.

On December 14, they did just that — putting the Aakash on sale for the absurd price of 2500 rupees, or around $47, hoping to move 100,000 units over the course of 2012. That figure was seen as staggeringly optimistic, since it represented 40 percent of India’s total market for tablet computers. But as soon as the announcement went all, their call center was jammed with calls, and their website started crashing due to excess traffic, to the point where their Internet provider warned them they might be experiencing a malicious hack attack. Their initial inventory of 30,000 units sold out in three days. Within two weeks, they’d built up a backlog of 1.4 million preorders. According to CEO Suneet Tuli, that reservation pool is now over 2 million — and still going strong.

“We’re overwhelmed,” says Tuli. “If you talked to analysts a couple months ago, they’d have told you their forecasts for all tablet sales in India in 2012 was around 250,000 units. We were more optimistic: We thought the market was more like one million, and hoped we could do 10 percent of that. And now it looks like we could exceed that by 15 or 20 times.”

The shocking demand for Datawind’s $50 tablet underscores the fact that access to the Internet is no longer a luxury, but a utility. “For those of us who’ve been online since the early ’90s, being connected to the web is like having running water,” says Tuli. “When the power goes out at home, my kids don’t scream that the electricity’s off, they scream ‘Dad, the Internet’s down!’”

The Tulis had long believed that this was true even of consumers in emerging economies like their native India: The factor barring low-income individuals from the net wasn’t education or even infrastructure — it was, plain and simple, price.

“The media in India was reporting last month this supposedly feel-good story that the country now has 100 million active Internet users,” says Tuli. “But if you read more closely, you realized that they were defining ‘active’ as using the net once a month. If you were counting only people who accessed the Internet at least once every other day, the number drops to 48 million. That’s 4 percent of the Indian population. Four percent! On the other hand, India now has over 900 million mobile phone subscriptions. So 75 percent of Indians have access to some kind of wireless network, and some way of recharging mobile devices.”

That statistic didn’t just convince the brothers that India represented a massive untapped market; it also pointed to the fact that the nation’s path to Net nirvana would go the opposite direction from that of the West, where computing began with bulky, expensive desktops and shrank down in size and price to embrace notebooks, then tablets and smartphones. Internet access in India began with the smallest and cheapest device, the phone, and would grow up and out. Which meant that the key to winning the market wasn’t a device positioned as an inferior laptop alternative, but as a superior substitute for a cellphone.

“We’ve been working on low-cost Internet devices for years,” says Tuli. “And the biggest problem for us wasn’t the technology — it was the price point. We put products out there for $100, $150, and the numbers weren’t fantastic. But at $50, that’s the price of lunch for two at an Indian hotel.”

According to research firm IMRB, the median household income for the 75% of Indians living in urban areas is around $3750, putting a $50 device at about 1.3 percent of annual income. A $499 iPad 2 would cost nearly 2 percent of annual income for a family at the U.S. median household income of $26,364.

“For at least 200 million Indians, the Aakash would not be seen as expensive,” says Tuli. “And that’s an absolutely enormous number for us.”

But price alone wouldn’t be enough to make the Aakash a success. The key to unlocking Indian demand was creating a device that reflected the market’s unique preferences and restrictions — factors with which the Tulis, who were born in India and moved with their family to Canada as adolescents, had native familiarity.

The first design decision the Tulis made was to give the Aakash a full-sized USB port. “Most tablets out there have mini- or micro-USB ports, or even proprietary ports like the iPad,” says Tuli. “But the way that Indians carry around and manage data is the USB stick. Taxi drivers don’t own PCs, but they’ll carry around USB sticks because for 30 rupees — around 60 cents — a USB stick lets them download 100 songs from an Internet café. For 25 cents, they can download any movie you can imagine. A USB stick is how urban Indians carry their lives around.”

Tuli notes that call center operators, who make up the vast bulk of India’s emerging middle class, spend 80 hours a week in front of PCs but rarely have them at home — only 14 percent of urban Indians own PCs. “If you’re earning $200 a month, of which 40 percent goes toward food, you can’t be expected to buy a computer,” he says. “I asked our 40 call-center operators how many had a PC at home, and just three raised their hands. But when I asked how many of them had a USB stick in their pockets, they all raised their hands.”

The other decision was to focus the tablet’s wireless experience not on the current-generation standard, 3G, but on GPRS, which is about 10 times slower. “The cost of 3G in India is prohibitive, and the range and access is very limited,” says Tuli. “So for us, the key question was, ‘How do you get a reasonable full-featured web experience with GPRS?’”

Prior to Datawind, the Tulis had founded several other startups — the most successful of which was WideCom, which developed a wide-format fax system for engineers and architects. (Suneet Tuli even successfully got the Guinness Book of World Records to dub their product the “world’s largest fax machines.”) But WideCom’s core innovation wasn’t its hardware, but its proprietary data compression algorithms, which were capable of sending a three foot by 4 foot engineering drawing over a 9600 baud modem in less than 30 seconds.

Datawind made use of the 17 patents they’d obtained for compression and image rendering to ensure that the Aakash could deliver a 3G experience on a 2.5G connection. “So the experience you get on GPRS with our tablet is as good or better than the one you’d get on 3G in India,” says Tuli. “We built our tablet understanding that the default network it would run on is one of the slowest and most congested in the world.”

The acid test for the Tulis? Whether the commercial version of the Aakash could stream a full-length Bollywood movie on GPRS without stuttering or choking. (The initial build of 30,000 Ubislate 7s — created to government specs — were WiFi only, but all preorders will be fulfilled with the upgraded $57 Aakash Ubislate 7+, which will also feature a much-upgraded processor, a more advanced OS and better battery.)

“That’s the compelling proposition we saw,” says Tuli. “For the Indian consumer, it’s all about communication, connection and multimedia consumption.”

Of course, the Aakash isn’t the first attempt to crack the low-cost computing space. Back in 2006, MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte famously announced the launch of the One Laptop Per Child initiative, a nonprofit venture to create a $100 laptop for children in the developing world. OLPC’s lime-green XO-1 was released in 2008, to a raucous mix of acclaim and criticism. Though 1.9 million XO-1s have been shipped to date, the project is now widely considered a disappointment.

“OLPC was never able to even get close to $100 — they priced the laptop at $180, which is a huge problem; it made the initiative dependent on governments and charities,” says Tuli. “We came out of the gate saying, ‘We want to make a device that consumers want to buy’ — totally independent of government policies. The Indian government is subsidizing tablets for college students, but I think we’ve proven that the consumer is not waiting around for subsidies.”

Tuli also notes an anecdote about OLPC deployment in Cambodia, where the laptop’s reliance on a Wi-Fi mesh network meant that most remote villages effectively had no means of connectivity. “When they checked on those villages a month later, they found that elders were getting kids to hand-crank the batteries so that the laptops could be used as a light source. That was the killer app for the OLPC: Light.”

Negroponte has announced that the third generation of the OLPC, a sub-$100 tablet called the XO-3, will be demonstrated at CES — but the reality is that the shockingly successful launch of the sub-$50 Aakash makes future prospects for the XO uncertain.

“In Thailand, Yingluck Shinawatra — the country’s first female prime minister — made the promise to give one tablet PC to every Thai child a big part of her campaign,” says Tuli. “At a debate, one of her rivals asked where the money would come from to fulfill that promise. She brought up our project and said, ‘It’s simple — we’re going to buy those.’”

Dozens of other governments have also sent feelers out to Datawind, prompting the company to consider how to aggressively ramp up production on a global scale. “We’re not just talking about developing markets, either,” says Tuli. “We think we can make an impact on the digital divide right here in North America.”

The $50 barrier seems to have been the big milestone, but it’s not the only one. “The fact is, back in 1984, when I bought my first Mac computer, with a black and white screen and 5 megabytes of memory, it cost $5000 — and just the cable to connect it to a printer cost $50,” says Tuli. “If someone asked me back then if I thought a full-color computer with multiple gigs of memory could be sold for the price of a cable, I’d have said ‘No way. Never. That’s ludicrous.’”

The components used to make up the Aakash Ubislate 7 cost around $20. Given the historical trends, their cost should drop by about 50% over the next two years, and half again two years after that. Which means that by 2016, the world could be buzzing about the imminent arrival of the first $10 tablet.

“There are a few barriers that need to be broken, but similar ones have been broken in the past,’ says Tuli, before concluding with a statement that echoes fellow Canuck Justin Bieber: “If there’s one thing we’ve learned in this process, it’s that you should never say never.”